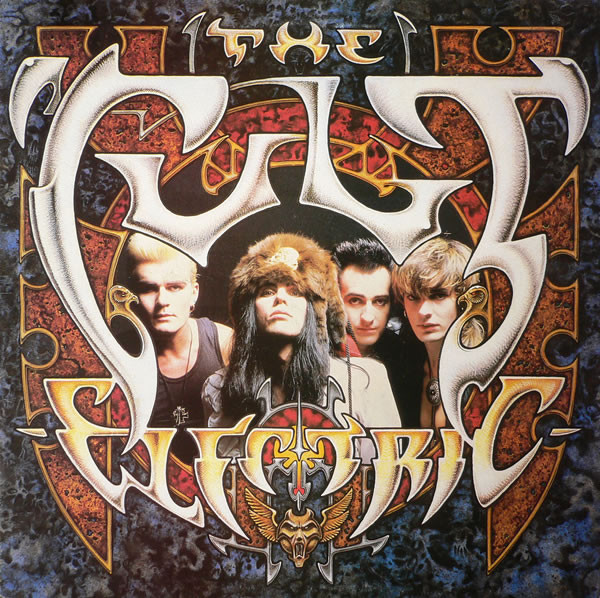

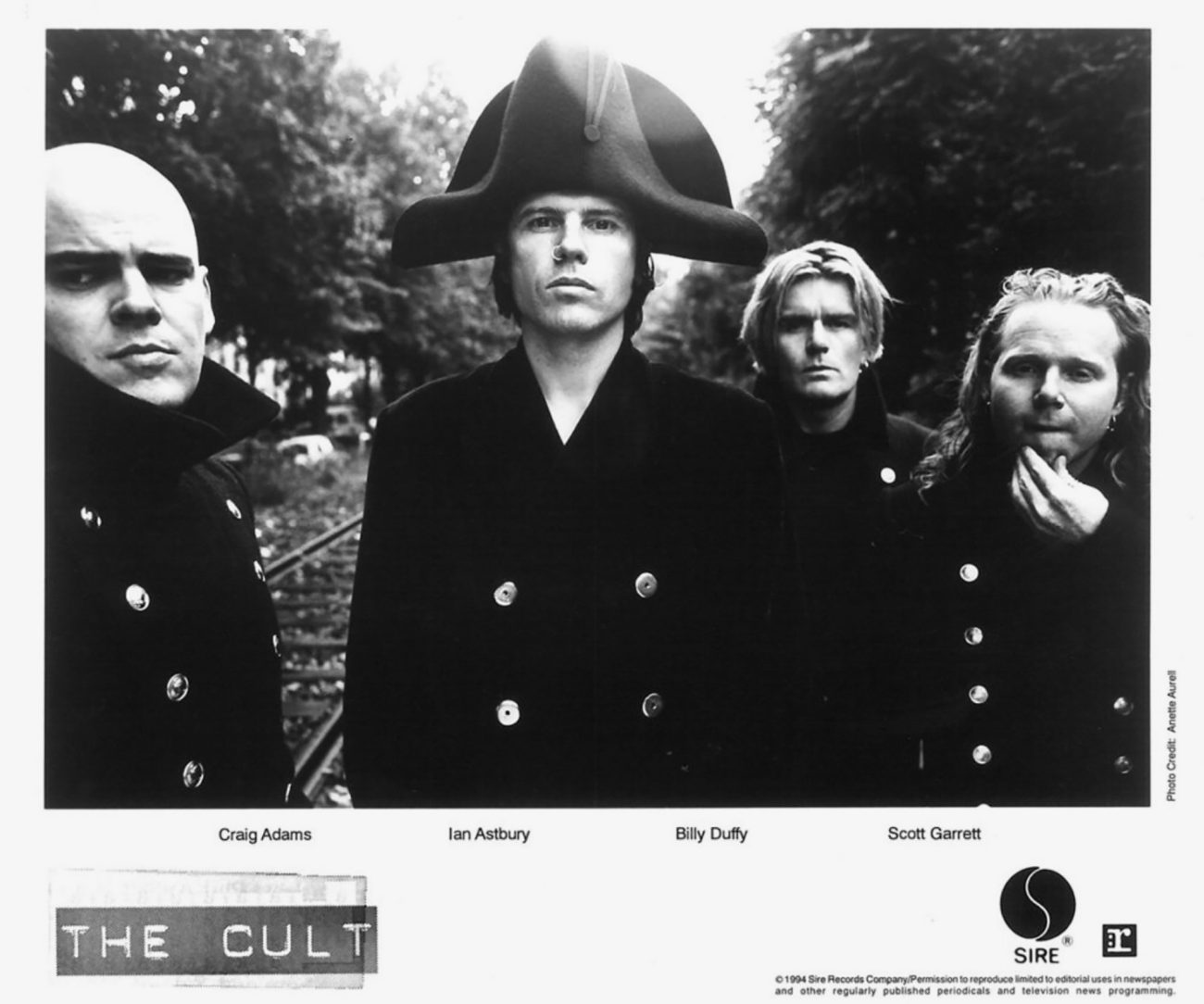

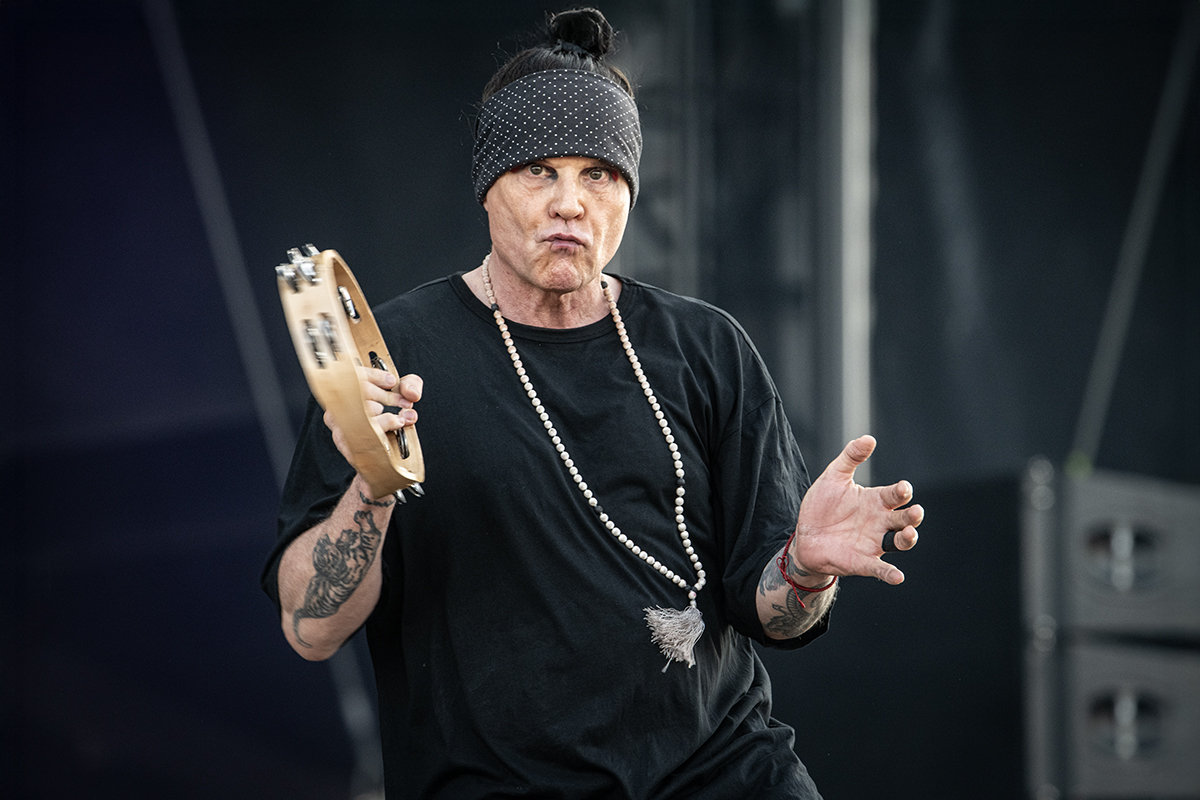

The Cult is a British rock band that kicked off in 1983, known for blending post-punk, gothic vibes, and straightforward rock ’n’ roll. The band’s core duo consists of singer Ian Astbury and guitarist Billy Duffy. Over the years, they’ve explored various sounds — from the moody atmosphere of “Love” to the raw, hard rock punch of “Electric” and “Sonic Temple,” as well as some more experimental albums, such as “The Cult” and “Hidden City.”

They’ve had massive hits like ‘She Sells Sanctuary,’ ‘Rain,’ ’‘Love Removal Machine,’ ‘Fire Woman,’ and ‘Edie (Ciao Baby),’ and while they’ve taken breaks here and there, they’ve always managed to come back strong. The Cult’s never really followed trends — they’ve just done their own thing. Their live shows remain loud, intense, and full of energy. Their latest album, “Under the Midnight Sun,” came out in 2022, and as of 2025, they’re still out there touring the world and making new music. They’re a proper rock band that’s stood the test of time.

In June 2025, The Cult finally returned to Finnish soil, performing at the Rockfest festival in Turku. I had the opportunity to sit down with the band’s guitarist and co-founder, Billy Duffy. We had an in-depth conversation covering almost everything about the band’s career — from The Cult’s early days to their biggest years of success, the ups and downs, the influence of grunge, various turning points over the years, and, of course, the band’s future. The interview is lengthy but definitely worth reading.

INTRO: REMEMBERING THE PAST VISITS IN FINLAND

First of all, Billy, welcome back to Finland after such a long time. If I remember right, it’s been about 15 years since The Cult last visited here. I still remember your show at the Sonisphere Festival in Pori — it was incredible, and the energy was absolutely electric. And of course, how could anyone forget that massive storm that rolled in during the festival? It really made the whole experience unforgettable!

Billy Duffy: Didn’t something happen afterward? Was there a storm after we played? I remember that, yeah. To be honest, I don’t remember much else — it was 15 years ago, after all. But I do recall there being a big storm, I think. Is that what happened? Did the festival get cancelled after that?

It wasn’t cancelled, but a few bands, including Mötley Crüe, had to pull out because their backline was completely destroyed.

Billy Duffy: Yeah, that’s what I heard, too. I remember that part, but I don’t really remember the show itself.

Anyway, your first show in Finland was in ’86 at the Provinssirock festival during the ‘Love‘ tour, if I’m right.

Billy Duffy: And that was in Seinäjoki. I remember that a little bit. Okay — a little bit. I was still drinking. But then again, so was everybody else. I remember Seinäjoki — we did that, because there’s a video of it online. If you go on YouTube, you can find us playing a song we’d just written — I think it was called ‘Electric Ocean.’ And you could tell it was the ’80s, ’cause we just played it live. Like, “Hey, here’s a new song we wrote. Let us know what you think!” I remember that — Provinssirock. And I’m trying to think of the other times… hmmm. I remember playing with Metallica somewhere in Finland…

That’s correct. It was 1993, at the outdoor arena in Helsinki.

Billy Duffy: Yeah, in ’93. That was just before I stopped drinking. I do remember that. And then we went to a club afterward, and there was a KISS cover band playing that night. We got up and took their guitars. I was so drunk, I couldn’t even tune mine. I remember someone tuning it for me. That’s about all I really remember, to be honest. But yeah, it was a lot of fun.

I remember seeing The Cult live with Metallica back in ’93. I was an old-school Cult fan, you know, from before the Internet days. And when I saw you on stage with the short hair and everything, I was pretty shocked, to be honest. Laughs

Billy Duffy: Oh yeah, ’cause you’d think we’d still look like we did in 1989, wouldn’t you? Yeah, well, that’s the point. Yeah, I get it. But The Cult, you know… have we ever actually played a proper show here? Like, a real gig in Finland at a regular concert venue? We’ve never done that, have we?

No, you haven’t.

Billy Duffy: So, it’s always just been festivals, hasn’t it? It’s interesting that we’ve never actually done our own headline show in Helsinki. People keep asking if we have, and I’m like, ‘Why do you ask me?’ Because I don’t know why. Honestly, I’ve got no idea. Maybe it’s down to logistics, really. Because if you’re in Stockholm and then Helsinki, you’ve got to go out that way, then double back — unless you’re heading further down. And we’d never played Estonia before, so we just did that for the first time.

How was Estonia for The Cult?

Billy Duffy: It was good. I enjoyed it. Yeah, it was solid. The crowd was great — proper loyal The Cult fans, you know.

THE CULT IN 2025

It’s 2025, and your current tour is called ‘8525.’ So, just briefly—what’s going on with The Cult this year?

Billy Duffy: Well, I mean, it’s sort of an anniversary tour, you know. I guess it’s some kind of celebration of… well, the name of it is just something Ian came up with. I let him do that stuff—he chooses all that. So yeah, he came up with that. And last year it was ‘8424’. So, I mean, it doesn’t really mean we’re playing songs from 1985, although the set has changed a bit this year. We’re playing more songs from “Beyond Good and Evil“, as well as some earlier material. We’re just doing it, really. I mean, we’re just having… to be honest, for me personally, I’m not taking it too seriously. I’m just having fun with it and playing the music that makes sense. Like, people are like… It’s hard to explain, really. We just stopped playing ‘Sweet Soul Sister’ because we were all sick of doing it. We’d been playing it for so long, and we were just doing it automatically. And I said one day, ‘Do we have to? Can we give it a rest?’ You know, Ian doesn’t really enjoy… that’s why we don’t do ‘Lil’ Devil’—because Ian doesn’t want to do it.

But you’re kind of lucky—because even though you’re not playing certain songs on this tour, you still have plenty of material to choose from.

Billy Duffy: Well, we’re lucky, really—fortunate that we’ve got enough material to choose from. And honestly, we’re just trying to enjoy it now, picking songs that work and actually inspire us a bit. The touring itself is more of a general celebration of the band’s music. You know, the whole ‘8525’ thing—it just means 40 years of the band. And that’s it. Nothing too deep, not very complicated.

I was just checking out the setlist for this tour, and I’ve got to say—it’s great. It seems like there’s at least one song from every Cult album so far.

Billy Duffy: Almost. Well, we don’t do anything from “Ceremony.” But honestly, we never really did much from that album. Sometimes we’d do ‘White,’ and sometimes… what’s the other song we played from “Ceremony“? Ian liked ‘Wonderland.’ But yeah, you can’t play them all. We take it on a tour-by-tour basis, you know.

In recent years, you’ve done several so-called anniversary tours, where you performed entire albums from start to finish.

Billy Duffy: We did a couple, yeah. Actually, we did three—the three being Love, Electric, and Sonic Temple, because they’re the strongest albums, you know.

While playing entire classic albums is definitely great for fans, isn’t it a little dull from a player’s point of view?

Billy Duffy: No, I actually like it from a guitar-playing point of view because each of the albums is consistent. So, I’m in a kind of zone. For me, I love playing just all “Electric” because I only have to be one guy—I don’t have to be picking for edge or trying to think about “Beyond Good and Evil“ versus “Dreamtime.” You know, they’re thirty years apart. I’m a very different guitar player between those periods.

So, for me, doing the set is very challenging. One minute I’m playing something from ’84, the next song is from two years ago. I find it hard. It’s hard to explain. It’s difficult for me. So that’s part of how the set’s structured—we build it so I get a stretch of time where I’m playing. Just personally, I don’t like swapping guitars every song. Well, there’s that—the tuning and all. But it’s also just mentally hard for me, physically too, to be the guy from 1983 and the guy from 2000 or 2023—all in the same space. Personally, I actually enjoy doing those full-album tours. They’re a bit of a relief. But I mean, we’ve done them now. The other albums aren’t quite as strong, so those three—that’s what we focused on.

UNDER THE MIDNIGHT SUN

The Cult’s latest album, “Under the Midnight Sun,” was released in 2022. If I’m right, most of it was written and recorded during the pandemic. Since the world was mainly in lockdown at the time, what was it like working on that album this time around?

Billy Duffy: Well, yeah, it was interesting because a lot of it was recorded in England while Ian was in America. So, that was kind of an interesting process. He stayed in Los Angeles, Charlie (Jones) and I were in England, the producer was in England, and the drummer we used was in England. So, it was a bit—it was interesting. I enjoyed making the record because I got to go and record in the countryside in England, which I really enjoy. And I like going to residential studios. So, I got what I needed out of the record in terms of enjoyment.

Ian and I wrote some songs in Los Angeles. However, the way things worked out, all the music was recorded in England, and Ian was just participating remotely via Zoom. Then he finished it up in Los Angeles. I don’t like working in Los Angeles. I think it’s a really bad place to work. I find it very distracting. I think it’s a great place to go and have fun, but it’s a terrible working environment. I’ve never liked working there. I just like the place, and I’ve lived there on and off over the years. I’ve spent a lot of time in Los Angeles, but I don’t like recording there. I just find it very, very hard work to clear your mind of all the bullshit fun and focus on the job. That’s my personal opinion.

So, the album was done like that. I really like the spirit of doing it as a gang, residentially. That’s something where Ian and I very much differ. He doesn’t seem to like doing that, although we did most of our records that way. They were all actually done like that. Even “Electric” was done like that. “Sonic Temple” was done in Canada like that. We didn’t live there. It’s being somewhere where you’re not at home. I like that process because then you can really focus on the music and stay in what I would say is like a bubble. I like that. It’s more just mental focus on the music and not on everything else going on around you. It’s just a personal thing. I just like to keep life very simple and put all my energy into the music for a month, not worrying about anything outside of real life. That’s what I prefer. It’s a personal choice. Honestly, I’d happily go and record on an island off Norway. But you have to have the songs. And I guess one of the honest problems with, as you become a band like The Cult, which has many, many years and 11 albums. The songwriting process is interesting. Ian’s got his own vision for what he wants out of The Cult, and I’ve got mine. And truth be told, they don’t always quite match up..

Maybe that’s one of the reasons that makes The Cult a unique band.

Billy Duffy: Well, that’s the secret — the struggle. But if it’s all struggle, that’s a problem. Too much struggle isn’t fun. So, you’ve gotta hopefully find that middle ground where there’s some creative tension, but also some excitement.

NEW CULT MUSIC

Ian said in a recent interview that ‘Several recordings are nearly finished‘ and that ‘There will be The Cult music this year of some description.‘ Does that mean we’ll be hearing some new music from you guys soon?

Billy Duffy: Well, Ian says a lot of things. I don’t even know if he’d remember saying that. I’m always writing music, but as far as I know, we’re not actively engaged in recording anything. That’ll happen eventually, but I don’t know what made him say that.

Does The Cult have a record deal with a label at the moment?

Billy Duffy: No, but I’m sure we can get one. We always seem to find someone who wants to sign us — that desire always seems to be there. So, I don’t think that’s a problem. I think we just have to be in the right mental space as artists, as a band, to want to make a new record. We also need to figure out what the goal is, but I think that time is coming. We’ve done enough touring now — we’ve pretty much toured everywhere in the world that we can, give or take. So, what generally happens then is there’s downtime, and we go quiet. That’s when we start getting creative. Yeah, well, that’s what I think. So, I believe it’ll happen organically. It seems to happen on a cycle of every four years. Obviously, the pandemic disrupted things for everyone. But if you look at The Cult, since we got back together in 2006, we’ve sort of made a record every four years. So that cycle will come around again — you just have to wait and see. I know we’ll give it a go — I can feel it coming. But I’m not sure what he meant back then. Maybe he just had a vision for the year ahead.

THE CAPSULE IDEA

Back in 2010, The Cult announced, “First of all, check your calendar: it’s 2010, mate. ‘EP’ is old technology… So, we’re not releasing an EP. We’re releasing ‘a capsule.’” Do you still remember that?

Billy Duffy: Who said that? Ian?

Yes.

Billy Duffy: What a surprise. I didn’t say that. [Laughs] Well, capsules don’t make any money—that’s just a fact. You can’t really charge for them in a business model. A capsule’s a great idea, but it loses money. Therefore, someone must be willing to cover that loss.

In theory, artistically, a capsule captures a moment in time. But you’re still writing four songs—it’s basically an EP, like in the old days—same thing. And you can’t charge full album prices for it. So, what is it, then? You’ve put in half the effort of making a full album to create something that can’t generate proper revenue. Part of this is the music business, of course. There’s art, and there’s commerce. The capsule idea is great, and it’s nice to try and capture something immediate. I think what Ian was getting at—and I agree with him—is that making an album now takes such a long time that you almost lose faith in the journey, especially as you get older as an artist.

And what I mean by that is: you’ve got kids, responsibilities, and finances. When you’re young, all you do is focus on the band. But when you’ve got a life outside of it, there’s this balance between being a human being and being in a band. In my experience, it just takes longer to create. And if Ian wrote all the songs, that would be easy. Or if I wrote all the songs. But neither of us does. We write together—and that’s what makes The Cult The Cult. It’s a delicate process. He just thought the idea of an album was dead, and in a way, it kind of is. But on the other hand, it’s still something that people do.

The Cult was somewhat ahead of the curve with that idea, and a few other bands also gave the idea a try. Like Skid Row—they split one album into three parts and released them separately. Although it wasn’t a very successful test, I still give them props for trying something different.

Billy Duffy: It’s nice to try, but from a commercial standpoint, we’re still mainly focused on the album format, which now really just means vinyl, produced in limited quantities for collectors. We’ve always released vinyl; I mean, every single record we’ve ever made has come out on vinyl—even “The Cult” in ’94 and “Beyond Good and Evil.“ That was a bit unusual because it was released on Atlantic Records. That’s actually the only major label we’ve ever been with, and only for that one album.

But vinyl—that’s more like art, you know? People buy an album because they appreciate the artwork and the collectible aspect. Still, I think it’s important. I believe it’s good to try creating new music, as long as you’re satisfied with the results.

However, I do think it was good that you gave the capsule idea a shot. When I met Ian in London at the time, I told him I didn’t think it would work, even though he seemed genuinely committed to it.

Billy Duffy: Well, you can disagree. It’s okay. I disagree with him a lot. [Laughs]“

THE EARLY YEARS OF THE CULT

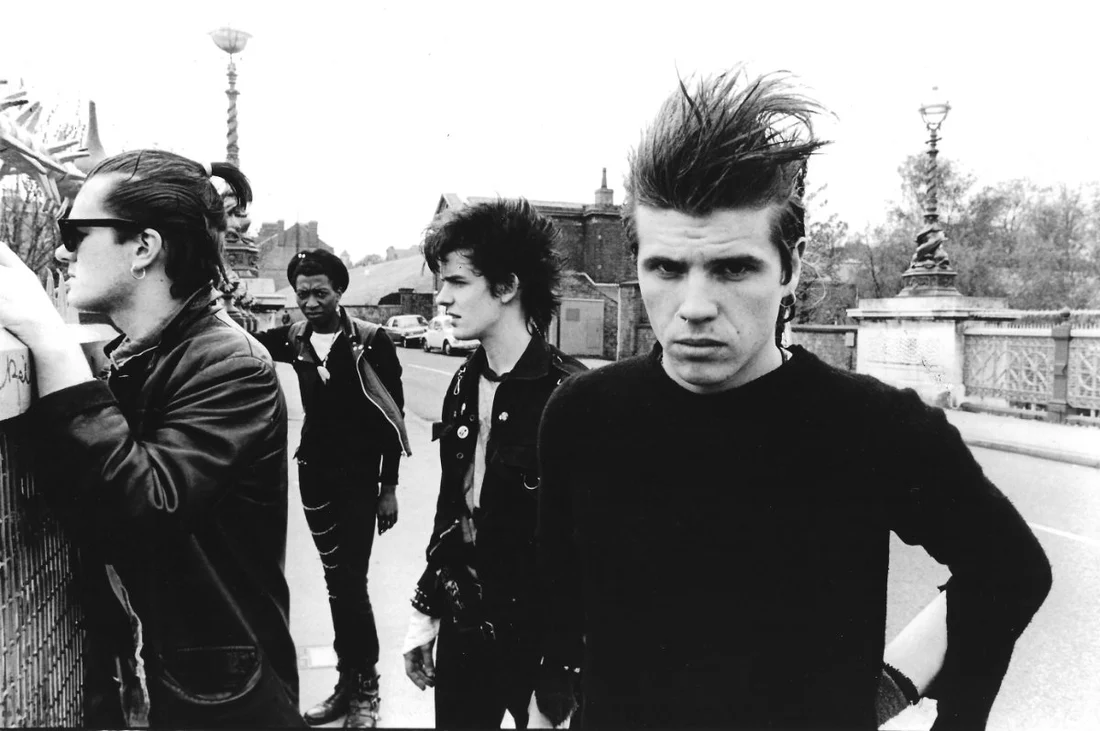

Thinking back to the early years of The Cult’s career in the UK, what do you think made you stand out from other bands at the time? I remember Ian once saying, “Yeah, we’re like Big Country, but better.” Do you remember him saying that?

Billy Duffy: Wow, that sounds like something Ian would say. ‘Laughs.’ What do I think about that? What set us apart from the other bands? I think we were always a bit more rock than the other guys. We were kind of a dark, gothic indie band, but we always had rock music in our DNA—and I mean classic rock. For me, it was bands like Free and Thin Lizzy.

You know, we all liked punk rock, and we liked the same kind of music, but more so than a lot of other bands, I think we had the ability in our DNA to become a rock band. And we kind of did that in America, you know? That was the journey. So yeah, it was always there. I think when we started, we were just finding our identity—two guys from two different bands trying to create a sound and a vision. That was the beginning of The Cult: figuring out, ‘Who is The Cult? What is The Cult?’ It’s not like we grew up or went to school together. We were two guys who liked and respected each other. We both realised, ‘We don’t want to work with these other guys—we should work together.’ And once Ian and I teamed up, we were very focused. Very serious, and we worked really hard.

So in the beginning, it wasn’t like either of you joined an existing band—you started it together?

Billy Duffy: Yeah, it was the two of us together. He left Southern Death Cult and came up with the band’s name. At that time, I wasn’t in a band—I’d been with Theatre of Hate and had some success there, but I’d kind of been fired from that band. So, we both decided to team up and start something new.

LOVE AND SHE SELLS ANCTUARY

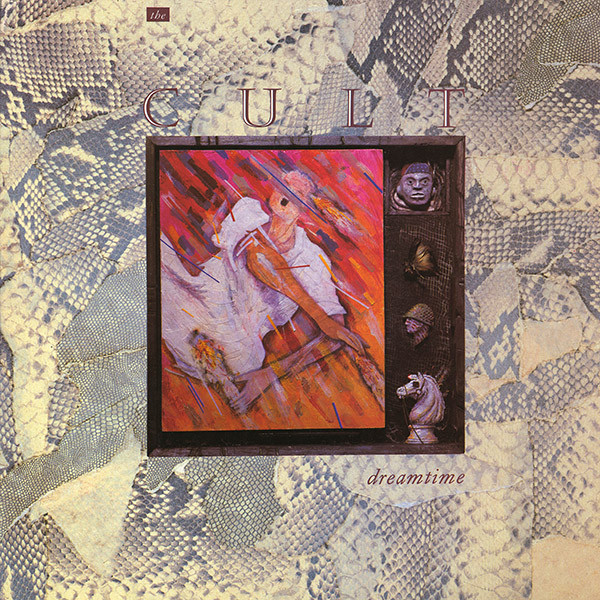

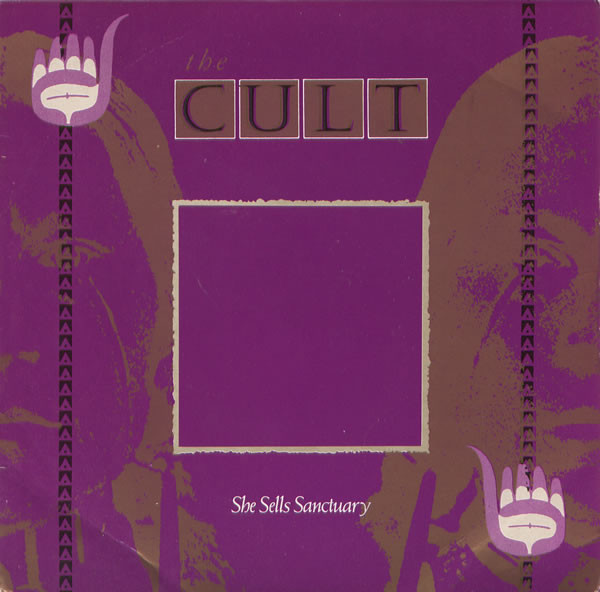

The Cult’s debut album, “Dreamtime,” came out in 1984 and got quite a bit of attention, especially with the single ‘Spiritwalker.’ But it was the next album, “Love,” and its single ‘She Sells Sanctuary’ that really made the band popular, especially in England. How important was that song and its success for the band back then?

Billy Duffy: Well, I think that’s a very good question, because there was life before ‘She Sells Sanctuary’ and life after ‘She Sells Sanctuary’—and we’re still living in the life after. I don’t think we’d be sitting here today without that song. That’s what I can say: that song changed everything. It’s funny you mentioned Big Country. I always bust Ian’s balls about this, but I remember bringing the song into rehearsals, and my recollection, personally, is that he was like, “It sounds a bit like Big Country, I don’t know…” But anyway, we did it, and it became a big hit. It changed everything for the band—forever. That’s what ‘She Sells Sanctuary’ did. It was a combination of luck and craziness that led us to be there. You know, the story with the producer—he wasn’t even who we wanted. Everything was an experiment. And it just worked out. Then suddenly, everybody went crazy for that song. There’s this kind of timeless sound to it now. It’s still played everywhere. I mean, it’s on TV in England every five minutes in a commercial. You can literally hear it 500 times a day over there.

ELECTRIC AND RICK RUBIN

Even though you were already doing well after the album “Love,” the next album, “Electric,” took the band to a new level. Do you think it would have ever become that popular without re-recording it with Rick Rubin?

Billy Duffy: No, it wouldn’t have. That’s exactly why we did it. We tried everything—we spent as much time and money as we could using the same producer as Love, which was a successful album, but only up to a point. Love was a success, but it was more like a first step. When we were working on the follow-up, we had already toured America extensively with “Love,” and we really appreciated the American rock scene. Rock was cool there—it wasn’t as tribal and divided as it was in England. So, when we came back, we knew we wanted to lean more in that direction. If you listen to the “Love” album, the last two tracks—‘Love’ and ‘The Phoenix’—were written just before we went into the studio. And those two added a bit more raw rock energy—guitar solos, heaviness—they hinted at the beginnings of something different. If you were to remove those two and replace them with some of the B-sides, “Love” would have been a very different album. Those two tracks were the marker—like, ‘Okay, there’s a rock band forming here.’ But when we attempted to move forward with the same producer for the next album, it simply didn’t work. We couldn’t get the right blend between the band and the production. And that’s when Rick Rubin came in and changed everything, with an American perspective, and by recording the album in America.

How big a role did Rick Rubin actually have on the album?

Billy Duffy: Huge. Absolutely huge. He changed everything—because we had already tried everything we could, and it still didn’t feel right. Then he came in with a clear, complete vision, and that made all the difference.

How much did you have to change the original song content when you started working with him?

Billy Duffy: The song content was the same. The songs were always there—we just adapted and trimmed them down. No new songs were written for it. The material was already in place; he just reshaped it.

Many artists have said in interviews that Rick is a really demanding guy in the studio—that he won’t let you leave until everything is done in the right way.

Billy Duffy: I think Rick makes the same record with everybody now, or even back then. He’s a genius, but he has one vision of how music should be. And if you can fit into that vision, you’ll make a great record. He needs songs, and that’s a really important thing people don’t understand—that Rick can only produce when you’ve got songs. He’s not capable of helping you write songs. It’s not really his job, but some producers do. Bob Rock is a prime example of a guy who can take ideas and turn them into songs.

I’ve learned that Bob Rock sometimes even plays instruments himself on albums if he’s not happy with how his clients are playing. “Laughs”

Billy Duffy: Well, it’s just a way to communicate, I think. With Bob, it’s a tool. I don’t think he likes to play, Bob—he just does it because he has to communicate an idea. But I think it’s something the public doesn’t understand. Sometimes, as a band, you have to make new music even if you’re not ready. And if you’ve a producer like Rick, who can only help you if you have a complete song, you need a producer who can help you take the… ‘Oh, I hear your idea. I get it. Well, let’s make this idea, that’s more… Yeah, Bob’s been doing that with a lot of bands. I mean, Bob Rock works and still works, and he’s been doing forty years of constant production. He’s very useful. He’s just different. Rick’s a genius, but he needs the raw material.

MOVING TO THE US

In 1988, The Cult moved to the US.

Billy Duffy: Yeah, yeah, that’s when we kind of relocated.

How important was the decision to relocate to the United States back then for the band’s career?

Billy Duffy: I think it was crucial from a commercial perspective. I think that we needed to really roll up our sleeves and have an American management. We changed management to an American manager, and I felt that, from a business perspective, being in America was necessary because we believed— though not everyone shared this view—that working hard in America would lead to a better career.

And that’s how it actually went.

Billy Duffy: And that’s how it went. If you’re big in Germany, it doesn’t mean you’ll get big in America, but if you get big in America, you’re pretty much big in Germany—and that was our choice. Plus, Ian used to live there, and he’s quite fond of North America, which I enjoyed as well. So, we kind of made the decision not to sacrifice Europe, but to focus on America, and we’d do Europe if we could. We were constantly working in America, touring there for months and months.

If you had stayed in the UK, you might have been stuck in just one area, right?

Billy Duffy: Yeah, I think so.

You’ve been living in L.A. for decades now, but as you mentioned, you still visit England frequently, and you even have a place to stay there. Are there any things you miss from the UK when you’re in America? Like some everyday stuff? You know what they say—‘Once a Brit, always a Brit.

Billy Duffy: Yeah, no, I still like it—I split my time between the two countries now. I try to enjoy the things I like about Southern California and the West Coast, focusing on the positives and leaving the negatives behind. And it’s the same with Britain—there’s a lot I don’t like. The taxes, the government, the way Britain’s run right now—it’s, to me, a proper horror show. Honestly, it’s like a circus over there. But I reckon I’m lucky I can do both.

Yeah, you’re in a good place now, because you can kind of just pick the berries off both cakes, you know?

Billy Duffy: Exactly, and I’m very aware I’m lucky I can do both. That’s one of the benefits, I suppose, of sticking with it. Because when you do, the sacrifices come early—I made mine when I was a kid. I spent all my time on the road. Ian and I devoted our whole lives—maybe twelve, thirteen years—to The Cult, to building the house of The Cult. After that, you can, you know, actually live a bit. But we didn’t lose—we just made a choice. And loads of musicians did the same thing. So now, I tend to dip into both worlds. And it’s good. California used to be a lot freer and more open in the ’80s. Now it’s got really busy—there’s a lot more meddling, politics, and rules. I used to love it because it was free, wild, and open. Everything was laid-back and fun. And now California’s kind of overpopulated, a bit heavy-handed, the politicians are a bit weird, and the taxes are sky-high… It’s kind of fucked, really.

Yeah, maybe that’s why so many musicians have ended up leaving L.A. and heading elsewhere.

Billy Duffy: Yeah, many have moved to other places, because it’s not just… I mean, it’s the politics and the tax together. If it were just politics, and the money was okay, but it’s both, so it’s kind of fucked up now. So, I’m lucky and I just float around now between both.

I recall the same thing happening in New York sometime in the mid-1980s. NYC used to be the place for bands and music, but then, everyone suddenly started moving out to L.A.

Billy Duffy: Yeah, L.A. was a bit of a backwater, and New York was the place to be. That’s where we went—that’s where I went, at first. As soon as I made a bit of money from The Cult, or Death Cult back then, I moved to New York in ’83 and stayed there. It was the place to be. But eventually it started to feel a bit old, and it was genuinely dangerous—properly scary. Still, it was interesting. Then, around the mid-’80s, L.A. sort of took over, and it just felt like all the energy had moved there.

SONIC TEMPLE AND THE BIG TIMES

The next album, “Sonic Temple,” was, of course, a massive success for The Cult—especially in the US—and one of the main reasons for its success was the support of MTV. What do you remember most about that era of the band?

Billy Duffy: Um, what do I remember? Well, it was an interesting time. “Sonic Temple” was a very good record of its time. It sounds like the era it came from—you have to put it in context. It’s probably a bit overproduced, but by the standards of the sounds of the 19… we recorded it in ’88, you know, but it came out in ’89. I think I always just wanted to be the lead guitarist in a rock band, playing stadiums, going around—that’s all I wanted. Very simple. That’s it. I had a very simple goal, so I got everything I wanted. I did it. So, I enjoyed all that. It wasn’t quite so easy for Ian, I don’t think. I’m not entirely sure that what was required of us to be that kind of stadium act—as people—I’m not sure whether it made Ian very comfortable. It seemed to me that the bigger we got, the more uncomfortable he became.

Personally, to a degree as well, I wasn’t very good at the… what would you call it… like the ‘being nice to people’ shit you’ve got to do—radio stations and all that. We were still a little wild. Still a bit feral. And we were doing these things, and people couldn’t understand why we were a bit nuts. And it’s like, well, we’re kind of ex-punk rock. We’re not Bon Jovi. We’re not smiling and happy. We are what we are. It was an interesting journey. However, it was great to transition from being a Gothic provincial band in England to playing shows in arenas around America. I mean, Alabama, Lubbock, Texas—10,000, 12,000 people coming to see us in Atlanta, Georgia. I was like, ‘What?!’ Even then, I still thought it was pretty amazing. It was really fun. I’m glad I enjoyed it.

Because of hits like ‘Fire Woman’ and ‘Edie (Ciao Baby),‘ along with MTV exposure and the promo shots taken at the time, made many people probably thought The Cult was part of the hard rock or hair metal scene at the time—but I don’t think that was ever really the band’s style or a goal.

Billy Duffy: Exactly, that’s spot on. I think those “Sonic Temple” promo shots made people see us in a certain way. But those pictures only showed one side of The Cult, because the band always had a much broader sound and vibe than just hard rock. It’s easy for people to box you in based on visuals, but there’s always been so much more going on beneath the surface with The Cult. We certainly looked the part, but musically, I think we weren’t really there at all. That was the thing. The thing is, as much as I enjoyed some of that stuff, we were never really part of that scene. I mean, you know as well that no one in The Cult ever wore spandex. We might’ve had the hair, but we didn’t… we were a rock band—more in line with Guns N’ Roses, Lenny Kravitz, Aerosmith, and The Cult. We weren’t Cinderella. I mean, by the way—I like Cinderella. We did a show in Canada with Tom Keifer, and yeah, they’re a proper rock and roll band. They’ve got that bluesy thing. I also like Skid Row — they were a great band. There’s loads of stuff I like, but I never felt like we were aligned with that scene. Sure, I saw those bands around, but we were always more of an organic rock ’n’ roll band.

You know how they say success always has a dark side—was that true for The Cult back then, too?

Billy Duffy: To me, there really wasn’t one. I just think Ian suffered a lot, but I mean, that’s really more to do with Ian. It’s not about the success—that was there.

So, Jamie Stewart—the original bassist—left the band after that tour. What led to that?

Billy Duffy: Jamie, yeah, Jamie did a lot. It was the lifestyle, really. He quit, and that was a big loss. It was sad that Jamie quit. He’d just had enough of the touring. He’d done his ten years, or whatever it was—nine years—and he just said, ‘I can’t do this anymore.’ He wanted to be at home. He actually said to me, ‘Good luck with Ian,’ when he left. So that was pretty funny. I was like, ‘Well, we’ll see.’ And here we are, 30 years later or whatever. But I still think that’s good advice: ‘Good luck with Ian.’ But Ian and I are kind of lifers. Rock and roll is like a life sentence to me. I’m doing this full-time. That’s what I wanted when I was a kid—that’s what I really worked towards doing. So, I’ll keep doing it as long as I can and enjoy it. And I still find… I try to find different ways to enjoy it. I had a lot of fun in the ’80s and the ’90s—I mean, too much fun, really. I had as much fun as anybody could possibly have. But yeah, I mean, I’m devoted to the process of still being a guitar player in a rock and roll band. That’s what I love.

WHEN GRUNGE RULED THE WORLD

Then came the ’90s—and with it, the rise of grunge, which really changed the musical landscape. I suppose it also ended up ruining many good things for numerous bands, including The Cult. You released the “Ceremony” album in 1991, but not long after that, things seemed to go downhill pretty quickly.

Billy Duffy: Well, that’s a very good point, because that did change everything for us, and for everybody else. And in a way, it was a good thing. The totally honest answer is, by the time we got to the “Ceremony,” neither Ian nor I were in a really good place. We were very separate. I wanted to continue making music like “Sonic Temple,” because we’d just had a platinum album. Why the fuck would you change? But he wanted to change everything. He wanted a completely different rhythm section, all this different stuff, and we were really quite apart. We’d also spent about a year and a half together on the road. So, we needed a bit of time apart, but they forced us to go and do a record.

We started working on Ceremony with Bob Rock, but then he couldn’t do it because he was embroiled in Metallica’s Black Album project. So, Bob said, ‘I can’t do this record with you.’ And that’s when it got bad, because then we got a nice enough guy, Richie Zito. He’s still actually a friend of mine, but he didn’t have what it took to make an album with Ian and me back then. Bob is strong. Most guys are just normal guys, but Bob is a strong human being—very Nordic and Icelandic. He needed that to get me and him to make something. And once we lost Bob Rock, we were fucked. And on that album, there are a couple of moments like, I mean, ‘White’, is okay. I like that song. But most of that album I think is shit. I just don’t like it. That’s why we don’t play it. The band, the sound—it’s the best guitar playing and the best sound that I’ve ever done, but the songs weren’t there because Ian was over there, I was over here.

And why? Well, grunge had happened. I’d heard Alice in Chains, and I was going, because I didn’t like the music that we’d written for Ceremony. I didn’t like it, really. I still don’t think it’s very good. It’s just not a very… and I’m not trying to just dump on it, but I’m just saying, honestly, it was an expensive mistake, and we should have taken a year off and just done nothing. And instead, we plowed on. The good news was that we went out on tour, and Lenny Kravitz supported us. I had the best time ever. It was even better than the Sonic Temple -tour. We still had the vibe. The band was still big from the work we’d done on the previous three albums, so the tour with Lenny Kravitz around America was just the best fun ever. Too much fun, I can’t even tell you. It was just great. So that was good for me. We were still doing arenas. We were even bigger than we were on “Sonic Temple,” but the album didn’t sell.

Grunge—I mean, grunge was great, and it was necessary. But ever since then, and you know, I mean, it’s not for me to say this, but you’re clearly a good enough journalist to know how much we influenced grunge bands. I mean, Mother Love Bone became Pearl Jam, Soundgarden—listen to their first EP. I mean, it sounds like The Cult, but that’s great. We sound like other bands that influenced us. I’m not saying I want a pat on the back. I’m just saying, and obviously, I’ve played with Jerry Cantrell. I’m friends with a lot of these guys, and we… I think what The Cult represented to those guys was the rock band that they could relate to. That’s what Jerry Cantrell said, because Jerry was into metal, but Layne Staley was into The Cult, and he said, ‘Have you heard these guys?’ And Jerry was like, ‘No.’ And that’s how they came together, like a band, like that. They were like, “Oh, wow,” and that’s great, because a lot of those, you know, I love Alice in Chains, Soundgarden. Those are my two particular favourites, but I’m a rock guy—you’d think that—but I like grunge. The problem with grunge was what came after it. It kind of cleared away all the fun, and it just became really dull and like fucking… and it’s not really—music’s never really recovered from that.

THE CULT AND THE END OF AN ERA

“The Cult” was released in 1994, at a time when classic rock bands like yours weren’t as popular as they had been in the ’80s. But I suppose that was the same situation for many bands back then, wasn’t it?

Billy Duffy: Yeah, of course—we were definitely on a downer, but so were a lot of rock bands at the time.

That album sounded quite different from anything The Cult had done before. It seemed heavily influenced by the grunge movement and the new musical vibe of the time. Do you agree with that?

Billy Duffy: Oh yeah, very much so. What that was, I’ll tell you, I’ll be honest with you, because I’m in an honest mood today. I didn’t really want to make that record, but I’ll be totally honest with you: a large amount of money was involved for me in making the record. I tried very hard to find some common ground with Ian to make that record. We did ‘The Witch’ as a single for a movie, and that’s good; we still play it. Ian loved it. It was kind of Ian’s idea; it’s a Pink Floyd riff, really. We made that song—we did it with Rick Rubin. There was no drummer, no bass player; we used samples, and George Drakoulias played bass. So, I thought, ‘Oh well, let’s make an album.’ We tried to work with Rick again, but we didn’t have any songs to work with. So, then we had nothing, so we ended up with Bob Rock, due to the reasons I’ve explained to you before. He can help you make songs from ideas. We had lots of ideas and no actual songs.

So, “The Cult” album was just what I wanted to do. My part in the process was, once I’d committed to making the record, I said, ‘Right, I’m going to stop practising. I’m not going to play guitar anywhere like I did on “Ceremony” or “Sonic Temple.” I’m going to stop literally, I’m going to use all different weird guitars, I’m not going to double track, and we’re going to just do this album in a very, almost like method acting.’ We pretty much tore up the script after “Ceremony”—that album was done, and it just didn’t work. “Ceremony” didn’t work.. And so, I think that “The Cult” really worked, it’s a great album, I think, as an album, as an entire entity, is a great piece of music. And there was a lot that came with it — a ton of content, you know? I really like the record. I think also that music was very cathartic for Ian to get out some personal shit. I think the biggest difference is the lyrics, lyrical content and the intention, very personal on that record. Whereas I think if you listen, my opinion, a lot of “Ceremony,” and it’s a generalisation, but as a listener, a lot of it sounds like it’s just songs written about not being happy on the road. And nobody wants to hear that. And if you think about the songs, negativity is just not good.

THE HIATUS AND OTHER THINGS IN LIFE

Following the release of “The Cult” album and some touring, the band went on hiatus for several years. What was the reason to do that?

Billy Duffy: Yeah, we toured it, and then Ian just— I think Ian’s personal life got a bit out of hand. The other thing that happened was we had a very ugly lawsuit with the Native Americans, whose kid was on the “Ceremony” sleeve. And it was really unfair, because we had bought the photo from a photographer, but he didn’t have a written release—it was a complicated situation. It’s not like we were doing anything wrong; we paid for the image. And then we got this ridiculous lawsuit for millions of dollars, which really soured the vibe. We managed to struggle through it and fight it, which took a lot of guts. I mean, it was many, many millions— just a ridiculous American lawsuit. So, that was a big weight on our shoulders. And then I think we were still touring… yeah, it just got too much for Ian, I think. And he left— he kind of left— and we went on a break for a while. But then he formed… well, I was confused, because I thought Ian had had enough of being on the road, but I think he’d just had enough of being in The Cult, because he soon formed his own band and was off doing his own thing. It was like The Cult, but not within. So, I’m not really sure what the point of that was, but yeah.

Maybe he just wanted to go back to the smaller circles at that point?

Billy Duffy: I don’t necessarily know if anyone wants to go back to being small. I’m not sure. Maybe. Honestly, I’m not sure about that. Yeah, I’m not sure. Maybe.

During the band’s hiatus, you kept a pretty low profile but also played with some bands. Could you tell me about that period in your life and career?

Billy Duffy: Yeah. It was just for fun. It was just friendship. It was just out of friendship. I wanted to just… I just hung out with people, and it was something to do. It wasn’t a career move for me, either of those things. I just enjoyed it.

You probably didn’t have pressure at that point to earn more money or go on big tours because you were doing well financially, right?

Billy Duffy: I was doing okay, I mean, you could always make more money, but I was pretty cool with it. So, I needed to find out who I was as a human being. You know, I’d always been ‘Billy from The Cult,‘ and we’d been on this journey from a little band to… well, nothing. And it was like, I just needed a few years. I actually went back to Britain and lived there for three or four years.

Where in Britain were you living at the time?

Billy Duffy: I was staying in London, and I also had a place just outside Manchester, so I was just living in the UK. I went to festivals, hung out—yeah, all that. It was just simple, simple stuff, none of that rock ’n’ roll, tour bus, hotel, or airport nonsense. I didn’t do any of that; I just played in these little bands for fun with people I liked, which is both good and bad, because if I do something, I want to do it properly. I do think the first Coloursøund record with Mike Peters is an extreme record. That’s a good record. That would’ve been the next Cult album, ’cause the music I wrote was meant to be the next Cult record. So, that Coloursøund record got a bit of muscle on it, the first one. So, I like it anyway. I think those were the ideas that were going to be on the next Cult record. Not all of it, obviously, because I’m writing with Mike Peters, but a few of them—you can hear there are signs of The Cult in there.

BEYOND GOOD AND EVIL AND BEYOND

Let’s jump next into 2001 and the album “Beyond Good and Evil,” which is, in my books, the best Cult album

Billy Duffy: Okay, that’s interesting.

That’s definitely a powerful comeback album. I still remember watching the video for ‘The Rise’ the first time and thinking, ‘What’s going on with the band?’ The song was great, but the sound was significantly different from the previous albums. So, what motivated you and Ian to start doing The Cult again then?

Billy Duffy: I like that album. I think it’s a good album. We got back together after I moved to England, but I’d still make trips to Los Angeles to see friends. I would stay with Matt Sorum because we were friends and we’re still friends. I would stay at his house for a month. He had a big house. ‘Come and stay. ’ And then we started talking. It was like, ‘Why don’t you get The Cult back together?’ Because he wanted a gig, right? And we talked about it. And then I eventually. It was a bit sad because I had Coloursøund with Mike, and that was doing okay. It was doing fine. But then I got a call from this manager guy representing Ian, and he said, ‘Do you want to get The Cult back together?’ So, Matt Sorum will tell you it was his idea.

However, the problem was that we couldn’t write any songs. The only one I remember us coming up with was a song called ‘Libertine’, which never made it onto the album. That was the first song we had. Somehow, it magically ended up being the first track, but it was only used as a bonus track in Japan. It was later released as a single about three years ago. It was like that, some kid called me and said, “I like your new single.” I was like, “What new single?” He went, ‘Libertine.’ Laughs. Anyway, I like the record. Bob Rock came in—at first, we tried another producer, but we just couldn’t get it together. The gigs were great; people were coming to see us, which was all good. But when it came to writing material, there was nothing there. We had lots of ideas and bits and pieces, but no songs. We only had ‘Libertine.’ Then Bob Rock came in and helped us out. I mean, Bob’s been really involved with our entire career, very, very much.

Yeah, I’m understanding now. Without him, the band’s career could’ve been very different.

Billy Duffy: Well, we tried other people, and it didn’t work. I mean, it works under certain circumstances, but Bob… there might be other guys like Bob, I’m sure there are, but for us, it was Bob. He helped us take numerous raw ideas and turn them into a cohesive whole. Bob had learned a lot by the time he did The Cult because we were one of the first bands he produced—before Metallica, before Mötley Crüe, he’d only done Kingdom Come’s debut album, which sounded good. I loved those sounds, you know? So, Bob came in with “Beyond Good and Evil,” and it was pretty… yeah, that was cool once we got it together. The whole thing was tuning the guitar down. Sounds like such a dumb thing to say, but that changed everything for me. As soon as I wrote all the songs with a drop D, I just got everything together. It was like a whole different thing, and I was like… We wanted to make a heavy record. I wanted… It’s a dark, heavy, gothic record, and I love it for that. I think that’s a great thing. And I love that muscle.

Besides ‘Rise’, there’s another of my all-time favourite The Cult songs on the album, ‘Burning Bridges.‘

Billy Duffy: I know the song. Laughs, it was probably a rock song that didn’t… how do I want to say this politely? I wouldn’t say those are the kind of songs Ian’s really into anymore. So, if your singer isn’t particularly motivated, they get pushed to the back burner, and you really have to fight to get the harder rock songs through.

As you mentioned earlier, that album was released by Atlantic, and in the end, it wasn’t a great deal for you at all.

Billy Duffy: It didn’t work out. We signed with Lava, which was founded by a guy named Jason Flom. The annoying thing was that fucking Clive Davis wanted to sign us, and he offered us more money, but we thought, ‘Atlantic, Led Zeppelin, Jason Flom’s a cool guy!’ So, we went with Atlantic. We should’ve gone with Clive Davis. I like Jason Flom—he’s okay—but we should’ve gone with Clive Davis, because he makes fucking success happen. Instead, we went with Atlantic, and they were a little bit like this… And then the 9/11 thing happened.

I find it somewhat amusing that the record company was unhappy with the album sales at the time, considering the album sold over 500,000 copies upon its release. Back in the ’80s, records used to sell in the millions, but these days, hardly any bands shift even 50,000. Times have definitely changed over the years.

Billy Duffy: They’d be thinking it was great. Yeah. I think that album did us a lot of good with the rock crowd. The guys who loved “Sonic Temple” and maybe “Ceremony” a bit—who maybe weren’t so into “The Cult” or not so into Love—the rock, the harder rock fans, liked that album. So that gave us a whole new lease of life.

Yes, I agree entirely – it was also great that you performed a lot of new material live during that tour, which gave the new song plenty of exposure.

Billy Duffy: Yeah, we did, yeah.

Did you also play the old songs from a lower key on that tour?

Billy Duffy: We didn’t… we just played the drop D songs in drop D. But we’d always been half a step down, just because most bands do. I did it back in the day because I’d heard it made you sound heavier. So, the guitar is tuned half a step down from concert pitch. Mostly, vocalists do it so they don’t get into trouble, but we did it really so Ian could get up there. But we got into the habit of it because I thought it added something. And then, of course, after grunge, you had bands like Korn and all those—Limp Bizkit and that lot—they were tuning down to C, and it became a whole different animal. But yeah, I enjoyed the lineup we had—with Billy Morrison on bass, Matt Sorum on drums. He’s a great drummer. They’re good mates of mine, and I enjoyed their company. But Ian just didn’t want to do it anymore. After that, he lost interest. He didn’t want to do it. And so, he ended up in The Doors, which he actually did very well with.

Anyway, that was kind of… that was a second break. But yeah, that was a good record. And then I get a phone call again in 2006—‘Hey, do you want to get the band back together again?’ Not from Ian, by the way, but… And in 2006, I was thinking like, ‘This time, I don’t know, man.’ Like, I really enjoyed doing “Beyond Good and Evil.” I was really happy doing that whole project. Nobody could help 9/11, but the band—well, Ian just vanished again, didn’t seem happy. So, this time I was a bit more sceptical. I said, ‘Okay, let’s do some gigs,’ because the songs are there, the fans are there—let’s just play some music. And then, of course, as soon as it was like, ‘Let’s do a new album,’ I honestly didn’t really want to make a new album back then. I’m not as into making new music personally as some people might be. It has to be—for me now, like I said at the beginning of the interview—it has to be with the right people, in the right place…

And you need to be in the right mood.

Billy Duffy: And the right mood. Otherwise, I just don’t want to do it. I don’t need to do it. But I’m happy to partake and contribute. And if I contribute, I do my best. I don’t just phone it in. If I’m in, I’m in. But I just want, that’s how I work. But I don’t want to make a new record just for the sake of making one—and I definitely don’t want to do it in L.A.

After all, you decided to make a new album and “Born Into This” was released in October 2006. Who actually produced the album this time?

Billy Duffy: Oh, well. “Born Into This” — it was produced by Youth. We did it in London, and I really enjoyed it. Ian and I did some demos in L.A., and I knew Youth was a good producer. Youth is really good. He’s got this reputation for smoking loads of weed and being in Killing Joke, but he’s actually fucking good. The next album he did after ours was Paul McCartney’s. Youth’s the real deal. He’s great. And I actually enjoyed doing that record. We did it in London with Youth, very quickly, and he had a good work ethic. I liked doing that. That was cool.

When I listen to that album now, I’d say it’s kinda a mix of two totally different types of songs. Yeah, half of it’s rock songs, and the other half’s something completely different.

Billy Duffy: Yeah. Half of it is entirely something else.

Yeah, yeah. Still, it’s a good mix overall.

Billy Duffy: Yeah, I think it’s good if you can make both coexist. If it were all just one thing, it wouldn’t work.

THE FUTURE

You haven’t taken any extended breaks since “Born Into This.” Even though only three studio albums have been released since then, The Cult has been a consistently solid band, especially when it comes to touring.

Billy Duffy: Yeah, it’s just organic. There’s no breakup, no drama… me and him, we just found a good place—something that works. I don’t overthink it. I think we’ve both found a way to coexist and get the most out of The Cult. There’s always that idea—though I’ve never personally thought this—but, you know, guys in bands often go, ‘Oh, if I could just do my own thing, it’d be better.’ So off they go and do their own stuff. Sometimes it is better, sometimes it’s not.

Usually, it’s not better.

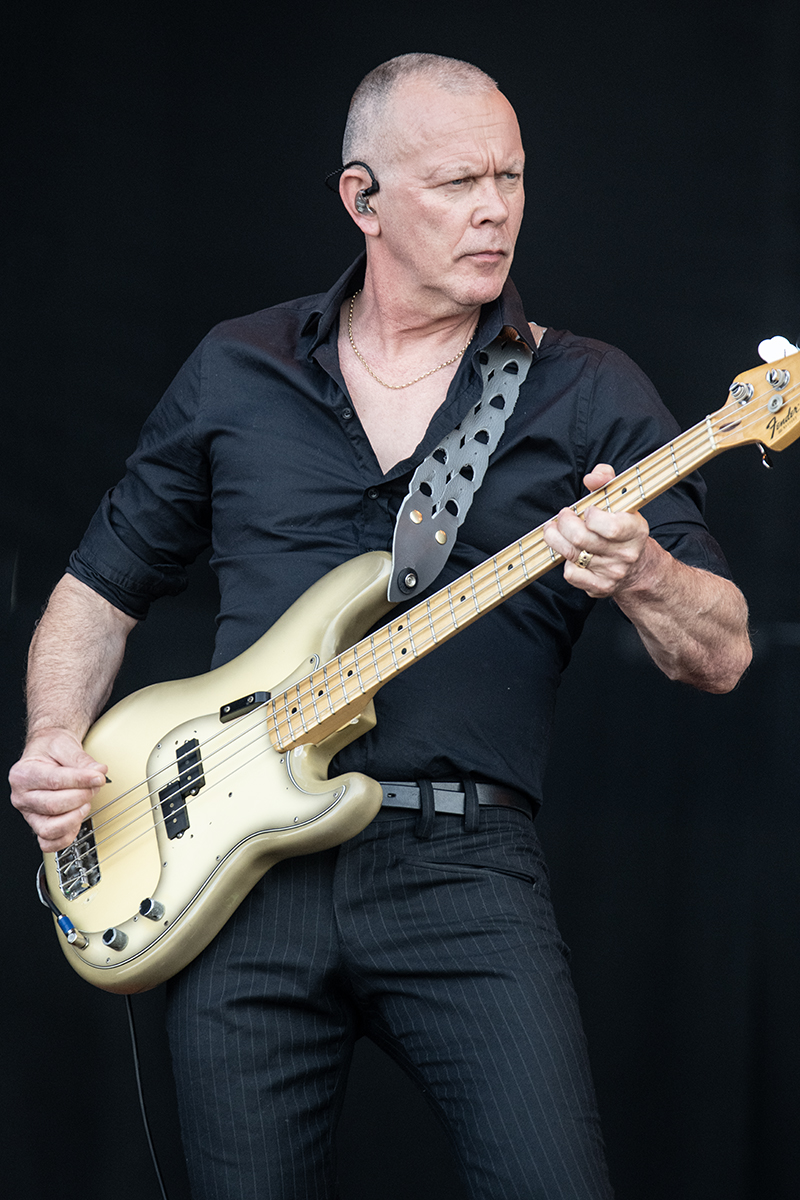

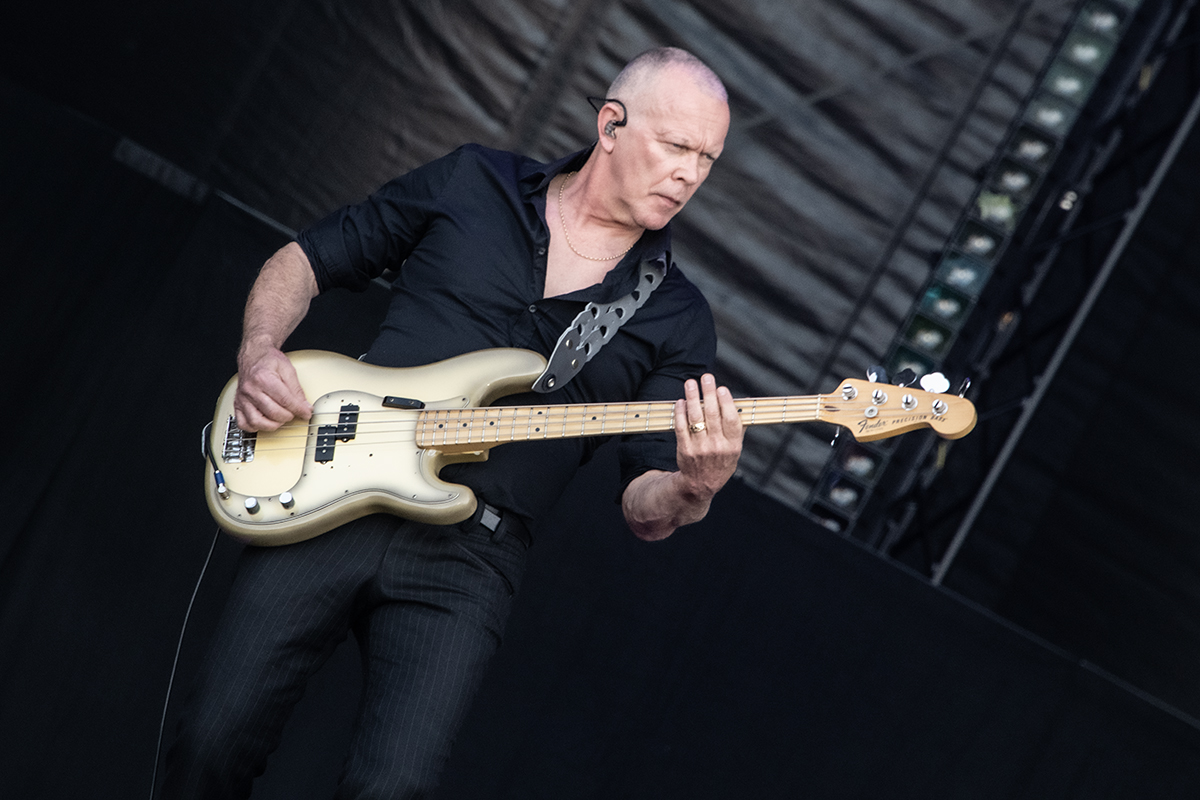

Billy Duffy: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Perhaps there’s an occasional exception, but generally it’s fine. I’m easy-going now. I enjoy playing. I really like the band. I really like Charlie Jones being in the band—he’s really helped keep it what it is these days. Yeah, he used to play with Robert Plant, and he’s been in Goldfrapp too, which is kind of funny. But I like that—I like the fact that his musical knowledge spans from Led Zeppelin to Goldfrapp. It’s good. It’s good that he can do that. And he’s a great guy—we hang out all the time, and he helps us a lot. He really brings a lot as a musician. If you’re running a band, you want people who can bring something, not just take. You want someone who contributes—not just ideas and energy and positivity—but someone who’s properly involved. Not just sitting there taking a paycheck. So yeah, Charlie gives, and that’s a very cool thing.

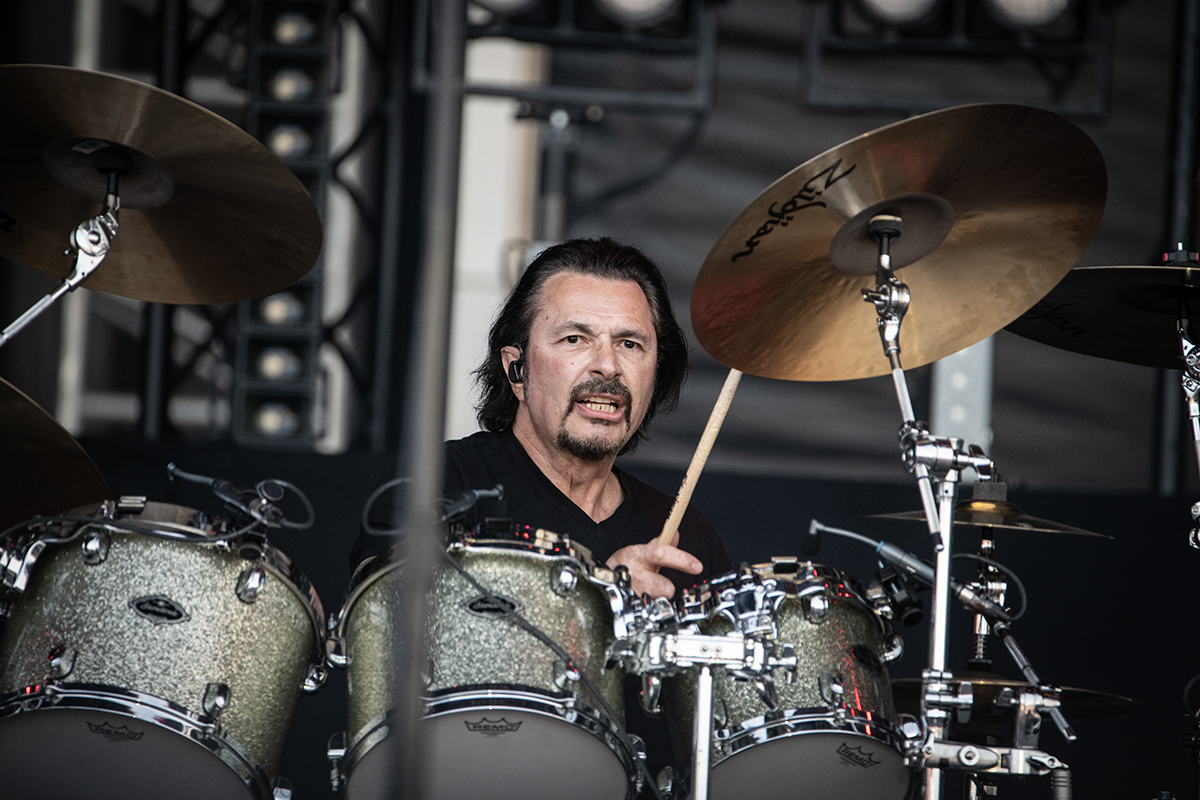

Another really important and loyal member of the band is the drummer, John Tempesta.

Billy Duffy: Yeah, John’s been around a long time, and he’s really steady. Proper professional—never missed a gig. He’s solid—a total pro.

I remember when he joined the band—I was a bit surprised, to be honest, given his background with bands like Exodus, Testament, and Slayer.

Billy Duffy: Well, it was a bit of a surprise to me, too. And to be honest with you, I didn’t really give it a thought, because it was 2006. I didn’t overthink it because I didn’t know whether the band would last more than two months. So, here we are, many years later, and we’re still going strong. So, you never know. I just kept an open mind. But when we got back together, I just said, ‘Well, let’s see what happens, man,’ you know?

Anyway, it’s been a long time since you all got back together in 2006—next year it’ll be 20 years. Time really does fly.

Billy Duffy: 20 years. Yeah, yeah. It’s crazy, isn’t it?

Our time is running out, so here comes the last question—once the current European tour wraps up in late June, what’s next for The Cult?

Billy Duffy: The future? Well, we’re talking… we’re looking at an American tour, ‘cause that’s the one thing we haven’t done in a while. We’ve been everywhere else. In 2024 and 2025, we visited Australia, South America, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Europe. And with Europe, financially, you have to… You can’t… I mean, we did Europe last summer, and we’re doing it again now, as best we can. And the only other place left for us to go—because we’re not really in a position to play places like the Philippines or Indonesia—is America. Japan, of course, we’ve always done; that’s one territory where The Cult always had a presence. But apart from Japan, we just need to do a proper American tour. So that’ll probably be the last thing we do this year—a full U.S. tour. And then I think we’ll be lying low for a bit. That’s probably when new songs would come around, if there’s going to be any. (Laughs) But there’s not going to be more dates. I know there’s an American tour that hasn’t been announced yet, but it’ll be announced very soon—and then that’ll be it. After that, it’ll be new material or whatever. Nothing for a while. So, we’ll see. I think I need to start getting ready for the show now. Are we good?

Yes, we are. Thanks again for doing this interview with me, and I’ll see you at the show!

Billy Duffy: All right. I’m glad we got to do it. I’m glad it worked out. It was good. Good fortune that we got to… You know, I don’t usually do interviews anymore. Ian generally does a lot of them or doesn’t do a lot of them. “Laughs”